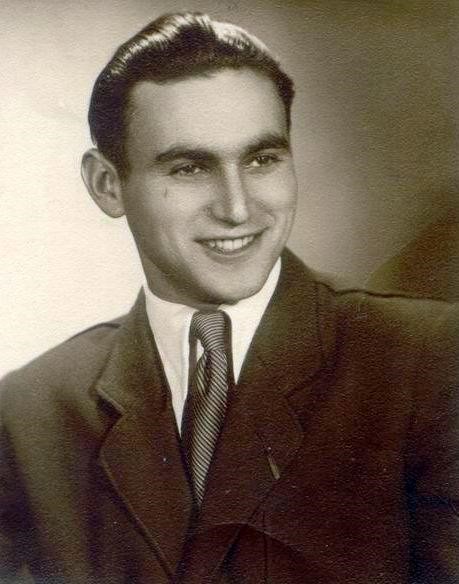

Rudolf Vrba

Rudolf Vrba escaped from Auschwitz-Birkenau so he could warn Hungarian Jews about their imminent extermination.

It was particularly urgent because I knew that all was prepared for the murder of one million Jews from Hungary. And because it was close to Slovakia, I thought it would be possible to give the warning.

You can download a PDF version of Rudolf Vrba’s life story here

Rudolf Vrba’s easy to read life story

Rudolf Vrba was born Walter Rosenberg on 11 September 1924 in Topoľčany in Slovakia (then part of Czechoslovakia). In March 1942 the 17 year old Rudolf demonstrated his unusually determined character by ignoring orders to assemble for deportation to Poland. ‘Naturally it didn’t come into my mind to obey such a stupid instruction’ he later said. Instead he set off to attempt to get to England. He was stopped at the Hungarian border and sent to the Nováky transition camp in Slovakia (where he made an unsuccessful escape attempt), and the Majdanek concentration camp in Poland, before arriving at Auschwitz I on 30 June 1942.

He was assigned to work at Auschwitz-Birkenau. After transports of Jewish people arrived and selections were made (with around 90% of the people being sent to the gas chambers) Vrba’s team cleaned the train wagons of dead bodies and sorted through the personal possessions that the people had been forced to leave behind. Vrba’s exposure to the process of transport and selection formed his opinion that ‘the whole murder machinery could work only on one principle: that the people came to Auschwitz and didn’t know where they were going and for what purpose’. Vrba decided that if Europe’s remaining Jews had knowledge of the industrialised slaughter at Auschwitz there would be resistance and panic which would hamper the Nazi’s orderly killing process.

In his role clearing the arrivals ramp, and in a later desk job, Vrba took mental note of the transports arriving, their origin, and estimated the numbers killed.

In early 1944 he learnt that the Nazis were preparing for arrival of Hungary’s entire Jewish population of around one million people, who were to be exterminated. Vrba had considered attempting escape from Auschwitz before, but now saw that it was now urgent. He felt the members of the organised resistance movement in Auschwitz were focused on their own survival, and not on provoking resistance from the people who arrived to be gassed.

Vrba worked with his friend Alfréd Wetzler to analyse previous unsuccessful escape attempts, and plan a successful one. Each daytime some prisoners worked outside the main camp fence, within an outer perimeter which was only guarded during the day. Vrba and Wetzler hid in a pile of wood, which they surrounded by strong-smelling petrol-soaked Russian tobacco, which they had learnt would deter sniffer dogs. When the Nazis discovered Vrba and Wetzler had failed to return to the camp they spent three days searching the area between the inner and outer perimeter. The search ended after the third day, and on the evening of 10 April 1944 Vrba and Wetzler escaped Auschwitz and began an 11 night walk south to Slovakia, 80 miles away.

After crossing the border into Slovakia the pair quickly made contact with the local Jewish Council. They were separated and interviewed about their accounts of Auschwitz independently, so the two testimonies could be compared and verified. A report was then written and rewritten, and translated into German and Hungarian, becoming a 40 page document.

The report contained descriptions of the camp, including detailed descriptions of the gas chambers at Birkenau and the process of extermination. Much of the report was devoted to painstakingly-remembered details of the transports which had arrived at Auschwitz – including the nationalities and numbers of those who arrived.

Throughout his life Vrba maintained that the leaders of the Hungarian Jewish community refused to publicise the Vrba–Wetzler Report to local Jews because they did not want to jeopardise negotiations they were having with the Nazis to try to save some of the community. Vrba was appalled as 437,000 Jews from the Hungarian countryside were sent to Auschwitz and murdered between 15 May and 7 July 1944. He believed many could have escaped as the Allied frontline was fast-approaching.

Despite not reaching most Hungarian Jews, the Vrba–Wetzler Report did make it to Switzerland, where it was published in the press. By June 1944 British and American media were reporting the reality of the Auschwitz-Birkenau death camp. World leaders made direct appeals to the Hungarian Government to stop the deportation of Jews. The deportations were halted on 9 July. Hitler was furious, but attempts to deport Budapest’s 250,000 Jews only resumed after the Hungarian Government had been overthrown by local Nazis in November 1944. By that time it was much more difficult to kill local Jews in an orderly way, with the war in its final stages, diplomats in Budapest working to rescue Jews, and greater awareness amongst Budapest’s Jews of what awaited them if deported to Poland.

Back in Slovakia the 19 year old Walter Rosenberg was protected by the local Jewish authorities, and given identity papers for ‘Rudolf Vrba’ – the name he adopted for the rest of his life. Vrba joined the Czechoslovak partisans and fought with distinction.

After the war he studied biology and chemistry in Prague. He married his childhood friend Gerta, though the relationship quickly broke down. Vrba escaped communist Czechoslovakia by defecting whilst on a visit to a scientific conference in Israel. He left Israel after a couple of years, as he was not comfortable living among some of the leaders of the Hungarian Jewish community who he blamed for failing to raise awareness of the mass killings at Auschwitz. He moved to Britain, and then to Canada, where he remarried.

The Vrba–Wetzler Report was an important piece of evidence at the Nuremberg war crimes trials in 1946. Vrba sent evidence to the trial of Adolf Eichmann in Jerusalem in 1961, and was a witness at a trial of Holocaust denier Ernst Zündel in Toronto in 1985. He died in 2006. Throughout his life Rudolf Vrba was somebody who refused to stand by. In the most extreme and appalling situation he risked his life to try to prevent the killing of hundreds of thousands of people. It can be argued that through their contribution to telling the world about Auschwitz the heroism of Vrba and Wetzler saved the lives of tens of thousands of Budapest’s Jews.

For more information: