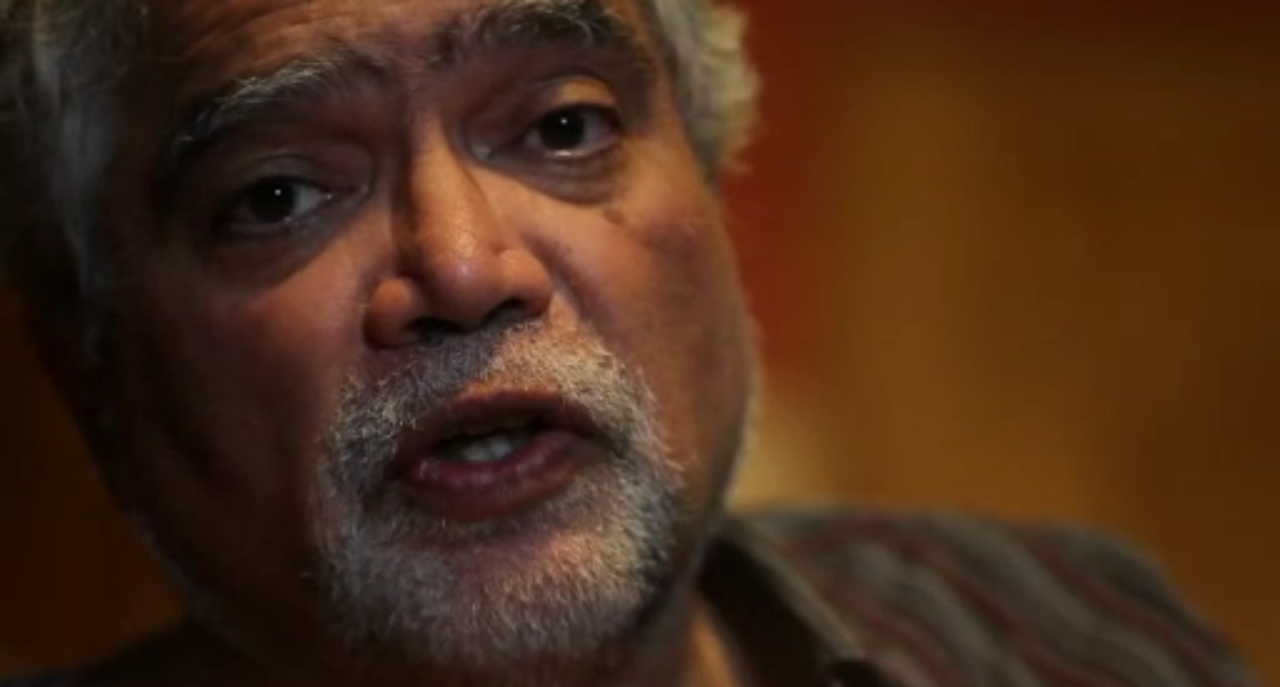

Untold stories – Mukesh Kapila

Mukesh Kapila was head of the UN in Sudan and witnessed the start of the genocide in Darfur. In April 2004 he alerted the international media.

As Head of the UN in Sudan in 2004, British diplomat Mukesh Kapila expected to see a peace deal ending Sudan’s 20-year civil war.

Then he started to hear bad news from Sudan’s Western region: Darfur.

[Mukesh is sitting in his lounge, talking directly to camera]

When disturbing stories started coming out of Darfur, it was really towards the middle of 2003 that we realised that these were not just isolated pockets of violence or a few killings; these were actually crimes against humanity being perpetrated.

If there’s one incident that really was for me the turning point, it was when a young Darfuri woman came to see me. This woman described how she had been raped along with a hundred other women in front of all their men folk. To be subjected to such abuse in front of your father, your brother, your son; what you are doing here is not just raping the women, you’re also raping the whole community.

So it was a feeling of helplessness more than anything else, that was my first reaction. Then an intense anger and an intense rage that this kind of thing had to be brought to the world’s attention. So I started on a round of diplomacy, and every capital I think I went to had access to intelligence information that I did not have, and yet they were doing nothing.

In fact what they said to me was, ‘Mukesh, stop being a nuisance, we are working on the north/south peace agreement. If you are too outspoken on Darfur then you’re going to compromise that particular agreement and we will be in a worse position.’

And the Sudanese Government of course knew this very well. I knew from my own personal contacts with the Sudan Government, including a senior official who said to me that they would not sign the peace agreement for North and South until the Darfur problem had had its Final Solution, and I had heard this phrase ‘Final Solution’ in other historical contexts and it sent a chill down my spine.

Washington DC was interesting. I was asking the Bush Government to actually allow this to be taken to the Security Council. A senior official at the White House said to me, ‘Yes, we are ready to do that, but we will not do it without the British.’ And the British were absolutely against going to the Security Council. And that made me extremely angry.

I realised that the success of my travels was zero, basically, in terms of any meaningful action. So there was only one thing left to do and that was, tell the story as I knew it, to anyone who would listen, anywhere in the world, as directly as possible. And there is only one way to do that. And that is through the media. And I knew that this would be the end of my career anyway. It was cold, calculated fury that was driving me towards the end because there’s nothing to lose; because everything had been lost. Most of all, the lives.

So I decided to come to Nairobi, which is the regional media hub of that part of the world, to tell through the BBC what I knew. And basically, there were three messages I wanted to say, one, that it was the World’s greatest humanitarian crisis, which it was at that time in early 2004; secondly, it was ethnic cleansing on a par with Rwanda; and thirdly, and this had never been said before by anyone else in public, or indeed even in private, that the Government of Sudan, the country to which I was accredited as a diplomat, as the Head of the UN, was committing these crimes against humanity. And once the genie was out of the bottle, there was no going back.

And it was interesting, it worked; because within three weeks of going public on it, the first Security Council discussions were meeting, and I think the first resolution setting up the peacekeeping forces was passed within about six weeks; in record time. Never before has the United Nations acted so fast; but of course too late, because the genocide was over, it was after the event in a way.

I think my drive, during the time I was there, and in the time since, is all about how to make sure that we reduce the chances of another Darfur happening. The only way to do that is to tell the untold stories.

We knew from day one what was going on. But those stories were not being told. It wasn’t lack of the stories, it was the failure to tell those stories, that ultimately led to the greatest tragedy of all.