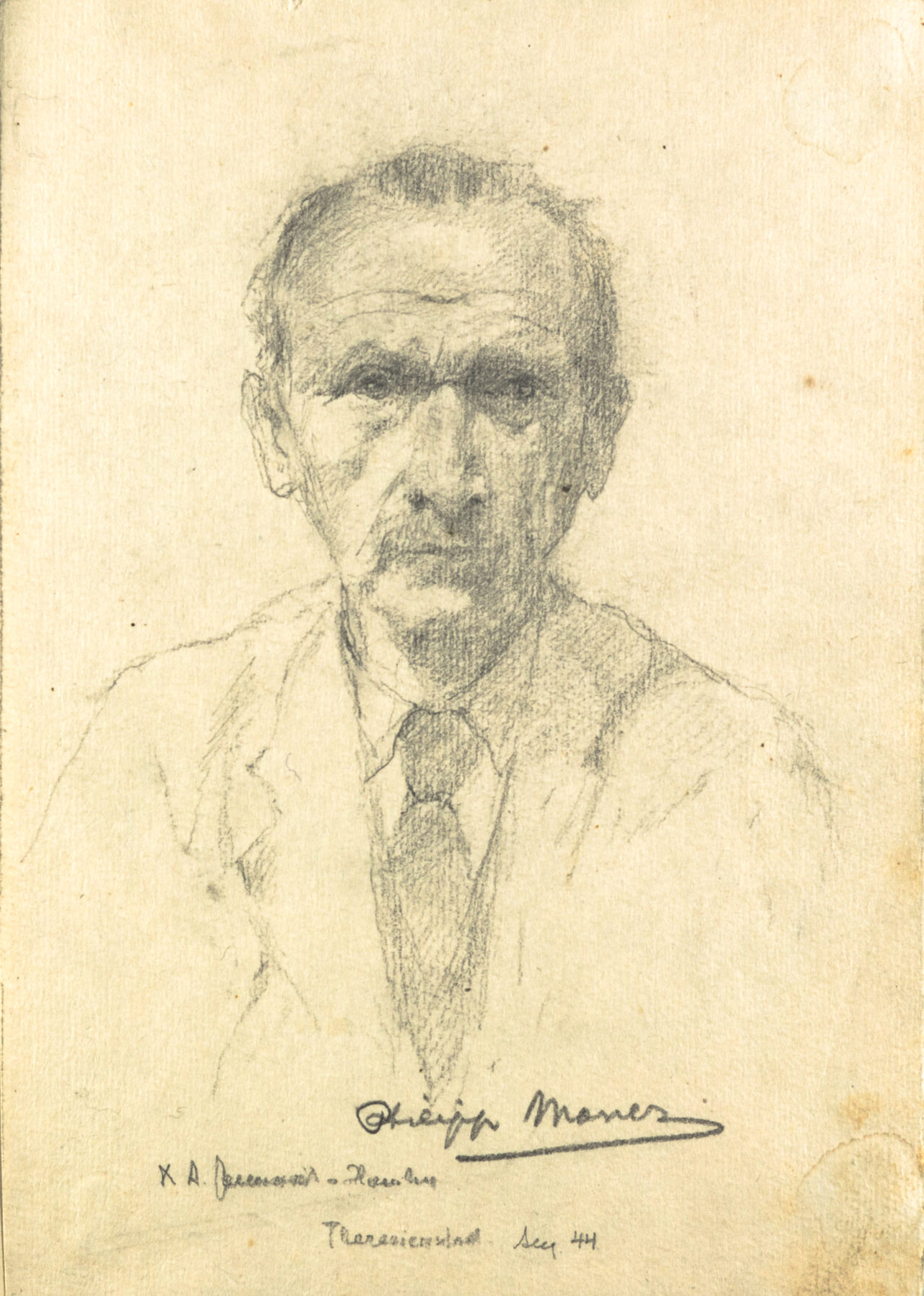

Philipp Manes

Philipp Manes was a German Jewish businessman and World War One veteran. In 1942 he was deported to Theresienstadt Ghetto, where he kept a meticulous record of daily life. He was murdered at Auschwitz in 1944.

The train advances one car at a time, as each is filled. Thus the Theresienstadt episode concludes, and 1,500 people pull away, [heading] to an unknown destination.

Philipp Manes (pronounced Mah-nes) was born in Germany on 16 August 1875, and spent most of his childhood in Berlin. As an adult, he travelled extensively and developed an interest in literature, music and theatre, before becoming a successful businessman. He married Gertrud Elias, and together they had four children.

During World War One, Philipp was drafted to the German Army and sent to the Russian front, where he ran several bookshops for soldiers. He was made a Sergeant and awarded the Iron Cross for bravery. After the war, Philipp returned to live with his family in Berlin.

In 1933 the Nazis came to power, and life became increasingly difficult for German Jews. Anti-Jewish legislation denied Jews freedom and restricted their rights. On 9 November 1938, Jewish shops and businesses in Nazi territories were attacked and destroyed, on a night which became known as the Kristallnacht. The following day, Philipp dissolved his business. In the weeks that followed, all of their children moved overseas, but Philipp and Gertrud could not be convinced to do the same.

Throughout his life Philipp was a keen writer, and from 1939 he recorded his experiences in detailed diaries. On 13 July 1942, Gertrud’s birthday, a letter was delivered informing them that they were to be sent to the Theresienstadt Ghetto. He recorded in his diary:

‘I told [my neighbour] about the envelope. “God help us!” She exclaimed in horror. “That means evacuation.” I was so frightened I didn’t know how to react.’

At this time, Philipp was a forced labourer at a nuts and bolts factory in Berlin. He appealed to his boss and a claim was submitted to stop the evacuation, but it was unsuccessful. Philipp and Gertrud were forced to give up their home and belongings and sign over their bank accounts.

‘The last three agonising days of our life in Berlin… are now behind us like an evil nightmare. It is indeed too painful to describe these busy hours during which we separated ourselves from property, possessions and people.’

They were deported by train on 23 July 1942 to Theresienstadt, a ghetto and concentration camp 30 miles north of Prague. On arrival, their bags were searched, and any remaining valuables and food were taken from them.

‘With fearful hearts we sat on the few narrow benches, waiting to see where our exhausted, broken bodies could finally come to rest’.

Throughout their time in the ghetto, Philipp continued to record their daily life in diaries. He and Gertrud received one ration of bread every three days. They slept in a stable with 50 other people until the end of the first summer, when they received a notice stating that men and women would be separated and relocated. Philipp was moved into a house with 240 other men. There was no running water and they shared just three toilets.

Theresienstadt was different from some other Nazi camps and ghettos. It was sometimes used by the Nazis as propaganda to convince others, such as the Red Cross, that inmates in their camps were not being mistreated. Therefore, the authorities tried to maintain the impression of normality for inmates by assigning them work. Around one month after his arrival, Philipp started working as head of the Orientation Service, helping people who were lost in the ghetto to get back to their accommodation safely.

On 21 September 1942, Philipp began organising lectures in the ghetto. They soon became a regular occurrence in which inmates shared their life experiences. They were so popular that Philipp went on to organise over 500 cultural events including lectures, readings and musical and theatre performances, all run by the inmates of Theresienstadt. Through the programme, Philipp met and recorded the experiences of well-known academics, lawyers, politicians and scientists in his writings.

‘Theresienstadt may be proud that its inmates came together as such a beautiful community to prove that in the ghetto art can unfold freely despite chains, and no narrow confines and no walls can cripple it.’

In 1944 the transports from Theresienstadt increased. Philipp’s diary entries describe the fear amongst inmates about what this meant, and where they would be taken to. The Orientation Service was shut down, but thanks to Philipp’s resilience and determination, the lectures continued throughout the summer.

‘I want to continue, to put my whole being into it to the very end and maintain the high quality of the evenings, in spite of the fact that so many participants are missing’.

By the early autumn the transports became frequent, with many of his friends and acquaintances sent to unknown destinations.

‘Theresienstadt is in constant motion – day and night. There are no more hours of calm. We… certainly know nothing and, indeed, live only on what we hear in passing.’

In his last diary entry on 28 October 1944, Philipp started writing the life story of a fellow inmate, Dr Leo Strauss. The account ends mid-sentence. From survivors, we know that on this day Philipp and Gertrud Manes were put on the last transport to Auschwitz with more than 2,000 others. They arrived on 30 October, and it is likely that they were taken straight to the gas chambers.

Of the 150,000 Jews detained at Theresienstadt from 1941-45, roughly 88,000 were sent on to extermination camps in Poland.

Before being deported, Philipp gave fellow inmate Lies Klemich over one thousand pages of his writings chronicling life in the ghetto. In 1948, the manuscript was handed to Philipp and Gertrud’s daughter Eva Manes. Eva donated the manuscript to The Wiener Library in 1995. His writings provide a remarkable account of life during the Holocaust, and a record of the lives of many individuals who were murdered by the Nazis.

Find out more:

Image credit: Portrait of Philipp Manes by fellow internee Arthur Goldschmidt, sketched in 1944. Image courtesy of The Wiener Library.

In this podcast Dr Klaus Leist reads excerpts of the book As if it were life by Philipp Manes.

[Duration 27.58]