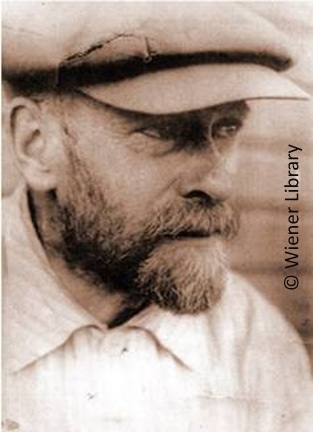

Janusz Korczak

Janusz Korczak was an inspirational teacher and writer who cared passionately about the rights and welfare of children. He founded an orphanage in Warsaw and stayed with the children through the Ghetto and transport to the Treblinka death camp.

You can download the PDF version of Janusz Korczak’s life story here

(Pronounce using a soft ‘ge’ sound, eg Korge-ack)

Janusz Korczak was an inspirational teacher and writer who cared passionately about the rights and welfare of children. His books were well known long before the outbreak of the Second World War. He had served in the Polish army, and was also a medical doctor; he had chosen to work in a hospital for the poor, so his earnings had been low. Korczak was an outstanding educator who, as early as 1912, spoke and wrote extensively about the right of each child, regardless of background or social standing, to be a happy and constructive citizen. He was committed to social justice and believed that education had a vital role to play in this, and gained an international reputation for what were then groundbreaking ideas.

In putting these ideas into practice, Korczak founded two large orphanages in the city of Warsaw, in Poland. One was in the Jewish part of the city. Korczak, who was himself Jewish, was Head of both. The orphanages was described as a children’s democracy; the children themselves decided who could stay and who could not, and had their own parliament, court and newspaper, in keeping with Korczak’s philosophy.

With Hitler’s rise to power came his invasion policies, and the Nazis moved throughout Eastern Europe. In line with their racist ideology, they evicted Jewish families from their homes and sent them to live in designated areas. These areas, the ghettos, were essentially large prison camps, controlled and well guarded. The children at one of Korczak’s orphanages were therefore among the hundreds of Jews enclosed within the Warsaw ghetto. Korczak had the option of staying with the children in his other Warsaw orphanage, since the ghetto wall now separated the two. However, he chose to go with the children in the ghetto because he felt that their needs were greater, taking on the task of looking after 200 Jewish children there, aged between seven and fourteen.

Conditions in the ghettos were appalling, where families were crowded together without adequate supplies of food or water. Many people died from starvation, disease and casual executions carried out by the Nazis. Eventually, the ghettos were ‘cleared’ and destroyed as part of the Nazi systematic attempt to rid Europe of all Jews. Those who had not already died were taken away to the extermination camps. Korczak could do nothing to save the children from his orphanage, since all Jews were marked for deportation. Eventually their turn would come and they, too, would be loaded onto a train and taken away.

Escape from the ghetto was virtually impossible, especially for so many children. If they could get outside the walls, the local population would have been able to tell where they were from and someone would have denounced them; the penalties for not informing on Jews were severe. They needed safe houses, false papers and a great deal of outside help, which was unlikely to be given. However, Korczak could have saved himself. Friends outside the ghetto, especially those who had been in his orphanage before the war had prepared for Korczak a secret room and false papers. An old Polish pupil, Igor Neverly, disguised himself as a sewer inspector and visited Korczak at the orphanage inside the ghetto. He begged his old teacher to escape with him into the outside world and live in hiding until the war was over, as he had so much to give in the post-war world. And yet, Janusz Korczak chose to remain with ‘his’ children. Hiding his own fear and helplessness, when the time came, he led the children in five orderly lines, quietly through the streets of the ghetto, to the waiting railway wagons, comforting the youngest and instilling courage in all. They were despatched in cattle trucks to Treblinka, a ‘death camp’ where arrivals were immediately sent straight to the gas chambers.

Although Korczak was not able to save his children from the Nazis, he did make a great deal of difference to those he comforted to the end, and to those who saw his example when the children were marched through Warsaw by the Nazis and onto the trains. While he lived and died at a time and in a place where the abuse of all human rights was on a colossal scale, Korczak’s greatest legacy is perhaps the inspiration he provided for the promotion of children’s rights worldwide, through not only his books, speeches and writings, but also by his personal example. Most of his ideas were included in the UNESCO charter for children’s rights after the war.