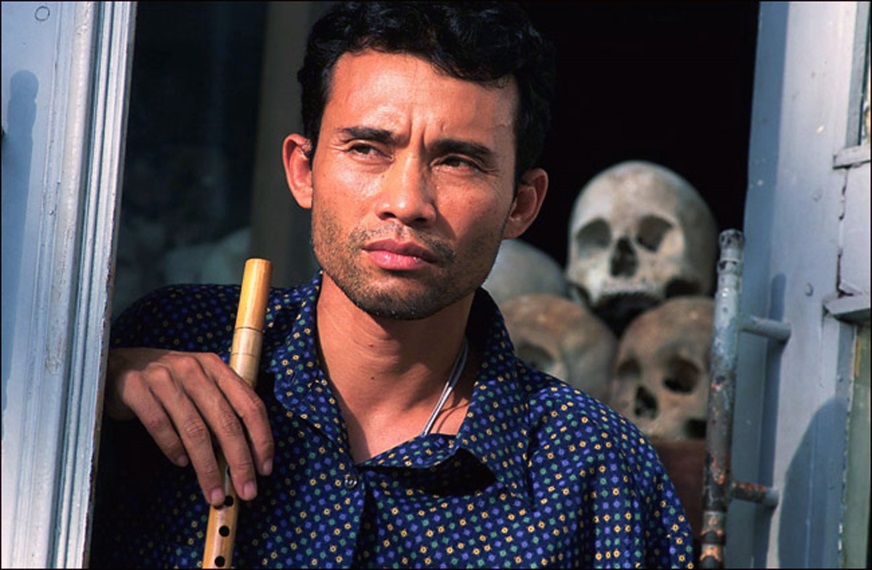

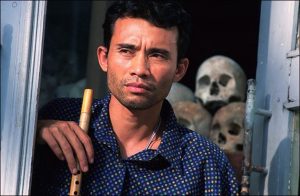

Arn Chorn-Pond

Arn Chorn-Pond was born in 1966 in Battambang, the second largest city in Cambodia, in south-east Asia. When the Khmer Rouge took over Cambodia, Arn was sent with hundreds of other children to a prison camp. He survived by entertaining soldiers with his flute-playing.

I come from a family of performers; I am the only one left.

Arn Chorn-Pond’s Welsh language life story

Arn Chorn-Pond was born into a family of performers and musicians who operated a small theatre in Cambodia’s second largest city Battambang.

Arn Chorn-Pond was born into a family of performers and musicians who operated a small theatre in Cambodia’s second largest city Battambang.

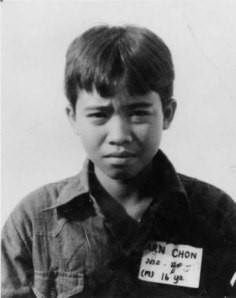

He was 11 years old when the Khmer Rouge swept to power in Cambodia in 1975, and by 1979 nearly two million people, a quarter of the population, were executed or died from starvation, torture or untreated disease.

Arn was separated from his family and forced to walk to one of the many work camps set up around Cambodia. He became a slave labourer in the forging of Pol Pot’s agrarian utopia.

It was on this initial walk that the horror began, with once cherished possessions left in the road, food scarce and people beginning to die. Arn says, ‘In just one day a person can get used to seeing dead bodies’.

‘They fall down, they never get up. Over and over I tell myself one thing: never fall down.’

Arn’s camp was a temple area that the Khmer Rouge converted into a ‘killing place’ where 700 children of around Arn’s age were forced to work from 5am to midnight with no food.

‘We were starving’, says Arn. ‘Three or four times a day they would kill people and force us all to watch. I was forced to push people into graves. If you didn’t do what the Khmer Rouge told you to do, they’d kill you too.’

‘During my time at the temple, in the middle of all the killing, the Khmer rouge forced us to play music’, says Arn. ‘They told us they were going to start a music class and asked who would like to play. So I raised my hand because I knew if I became a musician they might give me more food. And I knew I had a special skill.’

Arn learned faster than any of the other children, ‘Three of the other kids who didn’t learn as quickly, they ended up in the orange grove like many other people the Khmer Rouge killed’. Arn’s master, whose name he never knew, was allowed to teach them for five days before he too ended up in the orange grove.

Arn learned faster than any of the other children, ‘Three of the other kids who didn’t learn as quickly, they ended up in the orange grove like many other people the Khmer Rouge killed’. Arn’s master, whose name he never knew, was allowed to teach them for five days before he too ended up in the orange grove.

With death all around him, Arn survived, not only as a victim, but also a Khmer Rouge soldier. Like so many other perpetrators of the regime’s violence, Arn’s choice was kill or be killed. When, in 1979, the Vietnamese took over Cambodia, Arn says, ‘I was given a gun by the Khmer Rouge like thousands of other kids and I was told to fight’.

‘We were used as human shields’, says Arn. ‘I was in that war, full blown war, probably for about a year and then I ran away into the jungle of Cambodia and across the border to Thailand.

‘I was unconscious in the bush when five or six girls found me and carried me into a refugee camp.’

It was in the refugee camp in Thailand that Peter Pond, a Lutheran minister and aid worker, found and adopted Arn. In 1980 Peter took Arn to the United States where he initially struggled with the peculiarities of American culture, but with encouragement from his adoptive family, Arn found his voice – so much so that today he is a respected and inspirational speaker and campaigner for justice and human rights.

During the time of the Khmer Rouge, it was his ability to play the flute that helped keep Arn alive. Today, he says, Cambodian children enter a world that would have no music unless efforts were made to preserve it. ‘If nothing else’, he says, ‘at least they’ll have music in their lives.’

Today Arn Chorn-Pond lives in Cambodia.

For more information:

- Read about the Genocide in Cambodia

- A Song for Cambodia, Michelle Lord, 2008

- Never Fall Down, Patricia McCormick, 2013

- ‘An Interview with Arn Chorn-Pond: Helping Children in Cambodia Through the Revival of Traditional Music and Art’, by Arn Chorn-Pond and Michael Ungar in, The Social Ecology of Resilience: A Handbook of Theory and Practice

- The Flute Player, Dir. Jocelyn Glatzer, 2003

- ‘Cambodian played flute to escape death in Khmer Rouge labour camp,’ BBC, 6 May 2013

- Cambodian Living Arts

- FAQ about Patricia McCormick’s book Never Fall Down

- ‘Cambodian brings story of genocide to younger audience,’ Boston Globe, 8 November 2012

Photo: © http://www.usd.edu/press/news/images/releases/Arn_Chorn-Pond.jpg