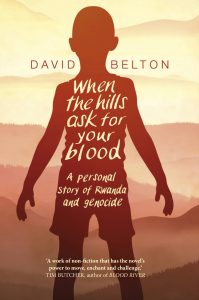

HMDT Blog: ‘When the hills ask for your blood’ book review

'When the hills ask for your blood' by David Belton is a gripping memoir presenting three different stories and perspectives of the Genocide in Rwanda.

The book introduces a Bosnian Croat missionary priest, Vjeko Ćurić, who helped rescue thousands of Tutsis, targeted for murder by extremist Hutus and a Rwandan man, Jean-Pierre Sagahutu, who went into hiding, and his wife Odette, who fled with their two children. Lastly, David Belton, the author of the book, working as a producer at the BBC in 1994 and one of the first journalists to arrive in Rwanda during the Genocide is the third character. The three separate stories intertwine with one another as their lives cross, although they all remain on distinct paths.

The book is hard to read at times, as Belton captures the intense emotion of those involved and the atmosphere around them so profoundly. As Belton and his colleagues are forced to stop at a roadblock and watch a man being hacked to death, he explains that ‘it was impossible to look away’. They realise that they are next. Even knowing that Belton clearly survived to write the book, the feeling still exists, and is an undercurrent throughout the book, that death – indeed murder – surrounds them and could strike at any time.

When the hills ask for your blood

Belton’s book goes beyond the end of the Genocide in 1994 to encompass the aftermath and the challenges that Rwandans faced, and still face, when it comes to justice, reconciliation and rebuilding. How does a country recover from such a dark period, when neighbours turned on one another, killing around one million people in 100 days, and leaving survivors to rebuild whilst living alongside the very perpetrators who killed their families? Belton tackles this challenging question head on, by revisiting Rwanda in 2004, and again in 2012-13.

On his journey back we are brought up to date with Ćurić, and Jean-Pierre and Odette; the good, the bad, and the challenges they face in coming to terms with the past. How do you recover from the trauma experienced during genocide? As a reader, it is satisfying to read a book that does not end when the Genocide ends, as many texts do. The events did not end in 1994 and the weight of the legacy is heavy. It’s poignant that, in his acknowledgements, Belton notes that there are a number of people who he is unable to publicly thank due to the current political situation in Rwanda. The country, though developing economically, still bears the scars of the Genocide in political, cultural and everyday life.

He discusses complex issues relating to ethnicity and cultural identity – the attempted unification of the country through a Rwandan national identity and the attempt to eradicate the ‘Hutu’ and ‘Tutsi’ ethnicities. But what does this mean for the country as a whole and the individuals, many of whom still struggle under the burden of the Genocide?

The book is beautifully written, as we travel though Rwanda’s thousand hills, and it makes for uncomfortable reading at times. The protagonists that we grow to know as we read the book are incredibly likeable – throughout the entire book it is difficult to resist the urge to skip forward and reveal their fates.

If you would like to read more about David’s experiences during the Genocide you can read the blog that David has written for HMDT.