HMDT Blog: Staff visit to Poland – the power of photographs

In April 2016, a group of staff members from HMDT went on a learning trip to Poland. Over three days, they visited Kraków and the site of the Kraków Ghetto, Oświęcim and Auschwitz I and Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camps. This is the last of three blogs written by staff about their experiences on the trip.

Genevieve

Images of the Holocaust and camps like Auschwitz are almost impossible to avoid; we are exposed to them in textbooks at school, on social media and in the many documentaries covering the subject. In the era of the smartphone, where few of us are ever without a camera and the documentation of everyday life is commonplace, we must not underestimate the importance of the images which came from Auschwitz.

Images of the Holocaust and camps like Auschwitz are almost impossible to avoid; we are exposed to them in textbooks at school, on social media and in the many documentaries covering the subject. In the era of the smartphone, where few of us are ever without a camera and the documentation of everyday life is commonplace, we must not underestimate the importance of the images which came from Auschwitz.

You will have seen the photographs of emaciated corpses, mothers holding the hands of their children as they walk unknowingly to their deaths and the despairing faces of starved prisoners. For me, seeing these photographs in a textbook at school was the first time the horror of the Holocaust truly struck me; six million became more than just a number. But the photographs from Auschwitz have a much greater purpose than just to shock.

Arrival of women and children at Auschwitz-Birkenau in May 1944

Although it is likely that we have all been exposed to them, photographs of Auschwitz as a functioning death camp are incredibly rare. When the Nazis fled from Soviet forces coming to liberate Auschwitz, they worked quickly to cover up their crimes, famously destroying the gas chambers and other incriminating evidence. In the exhibitions at Auschwitz I, we saw images of recent arrivals lining up for selection and being led off in different lines – one to be registered for slave labour, the other leading straight to the gas chambers. These photographs were from the ‘Auschwitz Album’ – an album of photographs taken by SS officials, which documented the process of the camp from arrival to selection, and finally the moments before arrivals were herded into gas chambers. No one is certain of why these photographs were taken, and no similar collection of photographs has been found since. Despite the huge body of personal evidence given by survivors of the camp, these photographs prove beyond all doubt the efficient and clinical process of death at Auschwitz. They confront those who seek to deny or downplay the Holocaust with evidence of the crimes which took place in that unthinkable place.

Other important photographs to come from Auschwitz were taken by Alex Errera, a member of the Sonderkommando, a group of prisoners who worked in the gas chambers and crematoria. In an act of brave resistance, a camera was smuggled into the camp. While another Sonderkommando member kept watch, Alex took four images, showing a group of naked women waiting to enter the gas chambers and bodies being burnt in a pit. Although these are not the clearest photographs to emerge, they are the only known photographs taken by prisoners from within the camp. As such, they confront us with the undeniable truth of the death camp, which the Nazis tried so desperately to conceal.

Seeing photographs of Auschwitz and visiting the camps are both important, but experiencing both together provides a complete understanding that neither one can provide alone. When we walked away from the crowds at Auschwitz-Birkenau towards the place where gas chambers and crematoria IV and V once stood, we found ourselves in a green wooded area near a small pond, with dappled sunlight through the trees.

This could be any wooded clearing, and you would be forgiven for thinking it beautiful. But next to the ruins of a gas chamber stood a sign with an unforgettable image on it – one of those taken by Alex Errera. Our guide asked us where we thought the photographer was standing when he took the photo. There is no better way to confront the truth of the horrors which took place than to stand in the place where it happened, seeing what the victims saw 70 years ago.

This could be any wooded clearing, and you would be forgiven for thinking it beautiful. But next to the ruins of a gas chamber stood a sign with an unforgettable image on it – one of those taken by Alex Errera. Our guide asked us where we thought the photographer was standing when he took the photo. There is no better way to confront the truth of the horrors which took place than to stand in the place where it happened, seeing what the victims saw 70 years ago.

Auschwitz-Birkenau: Jews deemed unfit for work waiting in a grove near gas chamber number 4 prior to their extermination

Another rare photograph from the Auschwitz Album stood in the exact location it was taken. It showed a group of men, women and children, sitting in a clearing adjacent to gas chambers IV and V, unaware they were about to be sent to their deaths. Without the context of the camp, I might have flicked past this photograph which seems to show nothing more than a group of people – apparently far less shocking than the images of piles of bodies we see taken after the liberation of Bergen-Belsen. But standing in that clearing, looking into the face of a young girl staring directly at the camera, I found myself confronted with real people – children, mothers, friends, people who lived – who would soon become that pile of bodies which so shocked me in my Year 9 history lesson.

Joe

When we think of photographs of the Holocaust it is often in terms of documentation. What can an image tell us as evidence? Is there something new we can learn or appreciate from a photograph?

When we think of photographs of the Holocaust it is often in terms of documentation. What can an image tell us as evidence? Is there something new we can learn or appreciate from a photograph?

Walking around Kraków’s Galicia Jewish Museum however, it’s clear that photographs can become much more than documentation alone.

With photographs taken by the late Chris Schwarz and accompanying texts by Professor Jonathan Webber, the museum’s permanent exhibition Traces of Memory: A Contemporary Look at the Jewish Past in Poland pieces together a picture of the relics of Jewish life and culture from across the region of Galicia (now southern Poland and western Ukraine).

Here, contemporary photographs illustrate five themed sections: Jewish life in ruins, Jewish life as it once was, sites of massacre and destruction, how the past is being remembered and people making memory today.

What is remarkable about the collection at the museum is the way Schwarz’s photographs often simultaneously capture both life and loss in one shot. Whilst we the viewer see a derelict synagogue or a now forgotten Jewish shop, we are encouraged to think of the life that once created and sustained that place. Whether it is through the remains of art on the walls of an abandoned building or the Hebrew words carved into stone, we are reminded time and time again of culture which was once commonplace and vibrant.

What is remarkable about the collection at the museum is the way Schwarz’s photographs often simultaneously capture both life and loss in one shot. Whilst we the viewer see a derelict synagogue or a now forgotten Jewish shop, we are encouraged to think of the life that once created and sustained that place. Whether it is through the remains of art on the walls of an abandoned building or the Hebrew words carved into stone, we are reminded time and time again of culture which was once commonplace and vibrant.

It’s a credit to the exhibition and the decision to only use modern day photographs that visiting the museum prompts contemporary questions and messages.

How many people walking around the streets of Kraków or many other Polish towns and cities would know of the deep roots of lost Jewish culture all around them? In our busy lives, when time for reflection is scarce, it is easy to ignore the past, even if it’s on your doorstep.

How many people walking around the streets of Kraków or many other Polish towns and cities would know of the deep roots of lost Jewish culture all around them? In our busy lives, when time for reflection is scarce, it is easy to ignore the past, even if it’s on your doorstep.

It made me think of all the times I’d been to different European cities where Jewish life once flourished without realising it.

Had millions of Jewish people not been murdered or forced away from their homes during the Holocaust, perhaps some of the places I’ve been would still be enriched with the culture on display in the photographs here. Perhaps the subject matter wouldn’t feel so unfamiliar to me.

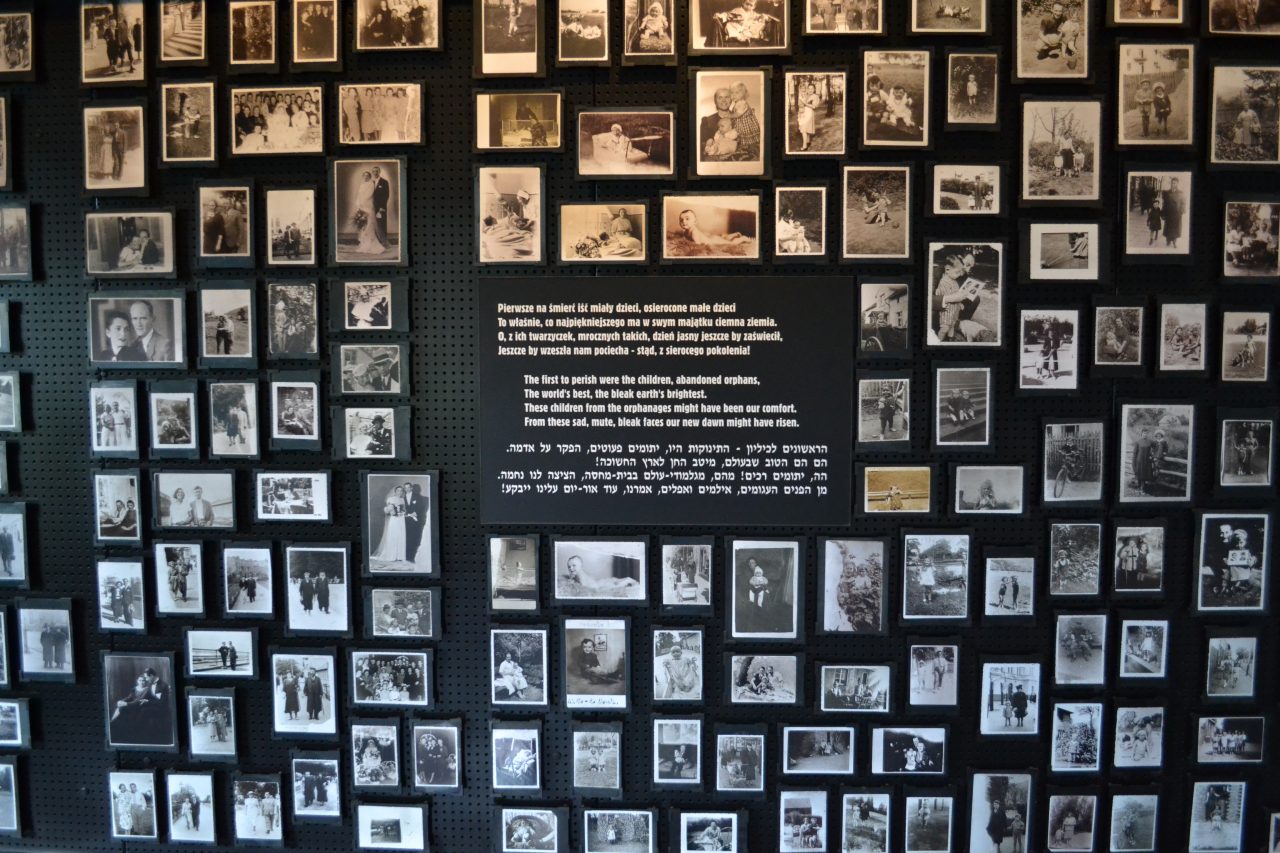

The following day on our trip we visited Auschwitz-Birkenau. In the block once used for processing new arrivals we came upon the rooms where personal possessions were confiscated; jewellery, clothes, family photographs and more. In rooms which were once full of fear and confusion are now displayed collections of intimate family photographs, taken from their owners upon arrival at the camp.

Here the photographs on display remind us of the individuality and humanity of the victims who were taken to Auschwitz. After a day in which I couldn’t help but think of my own family and loved ones, seeing these snapshots of happier times was tough.

In both these places, the photographs featured simultaneously tell us a story of life and loss. In Auschwitz we see examples of families and friends enjoying life, however when viewed in context we know of the awful destruction that came next. In Chris Schwarz’s images, traces of life can be found, but only by looking hard at the remnants of physical objects and settings that are often missed as we pass by.

In both these places, the photographs featured simultaneously tell us a story of life and loss. In Auschwitz we see examples of families and friends enjoying life, however when viewed in context we know of the awful destruction that came next. In Chris Schwarz’s images, traces of life can be found, but only by looking hard at the remnants of physical objects and settings that are often missed as we pass by.

Theft is at the heart of both these collections; family photographs in Auschwitz were forcibly taken away from their owners, just as the shops, businesses and ways of life in Schwarz’s photographs were stripped of the people who created and enriched them. There is no question, this was an act of cultural vandalism.

When we look at photographs, contemporary or historical, we should remember the power that they have to tell us so many different things. In both these cases, photographs have moved beyond archival documentation and thanks to their settings and the expert curatorship displayed, they offer an opportunity for audiences to reflect on bigger questions of memory and society.

The theme for HMD 2017 is How can life go on? Within that theme, we look at the importance of remembrance and loss of individuals and culture. The photographs of Auschwitz and the photography at the Galicia Jewish Museum confront us with this awful reality.

The HMDT blog highlights topics relevant to our work in Holocaust and genocide education and commemoration. We hear from a variety of guest contributors who provide a range of personal perspectives on issues relevant to them, including those who have experienced state-sponsored persecution and genocide. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of HMDT.

- Find out more about our theme vision for HMD 2017 here.

- See the ‘Auschwitz Album’ here.

- Find out more about the Galicia Jewish Museum here.

- Suggested reading: Auschwitz-Birkenau: The Place Where You Are Standing

- Read the first staff blog on the loss of Jewish life and culture in Poland here.

- Read the second staff blog on visiting Auschwitz here.

Photographs copyright Galicia Jewish Museum